Abstract: This paper addresses the operational challenges of large-diameter butterfly valves used in 2 m-class large-scale intermittent high-speed wind tunnels. An optimized design for a DN2500 hydraulic butterfly valve is proposed. Finite element analysis was conducted to evaluate the stress concentration and modal characteristics of the redesigned valve. The results indicate that the stresses at critical sections under extreme operating conditions satisfy the design requirements, and the vibration performance is acceptable. Engineering applications demonstrate that the butterfly valve provides reliable sealing performance, low flow blockage, and a low failure rate, thereby ensuring stable and long-term operation.

Intermittent high-speed wind tunnels require fast-acting valves in pressurized gas supply pipelines. Owing to their compact structure, light weight, compatibility with various actuation systems, and high opening and closing efficiency, butterfly valves are widely used in such facilities. Taking the CARDC 2 m supersonic wind tunnel as an example, this facility features a wide Mach number range, a broad dynamic pressure range, and excellent flow-field quality. As the largest supersonic wind tunnel in China in terms of test-section size, it experiences significantly higher aerodynamic impact loads than conventional intermittent wind tunnels, thereby imposing stringent performance requirements on the butterfly valve.

At present, the main problems encountered with butterfly valves include:

- Wear of the butterfly plate and its sealing surface

- Wear of the valve stem and bushings

- Loosening of the connection between the actuator and the valve body

- Displacement of the locating pin between the rotating shaft and the butterfly plate

- Poor contact performance of the closing surfaces

These issues arise primarily from complex aerodynamic loading conditions, including impact loads from frequent valve actuation, severe random nonlinear vibrations, material stiffness degradation, and cumulative fatigue damage. To ensure the safe and reliable operation of wind tunnel tests, this paper proposes an optimized design based on the original DN2500 hydraulic butterfly valve. The key structural components have been optimized to meet the specific performance requirements of large-diameter butterfly valves operating in intermittent high-speed wind tunnels.

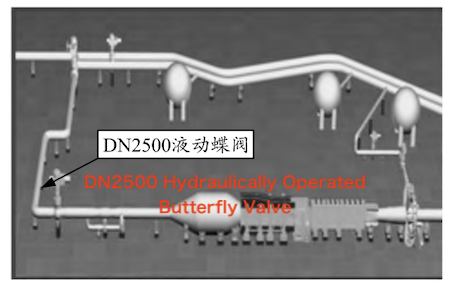

Fast-acting valves in wind tunnels differ significantly from conventional industrial valves because they operate frequently and are subjected to complex, highly variable aerodynamic loads. The main fast-acting valve in the 2 m supersonic wind tunnel is a DN2500 hydraulic butterfly valve, installed upstream of the tunnel, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Valve position layout

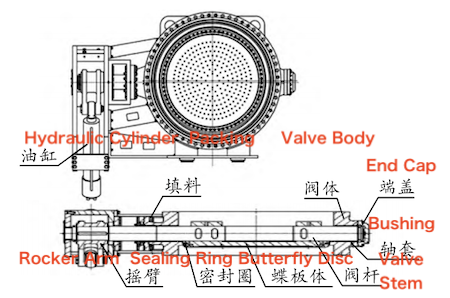

The structural configuration of the DN2500 hydraulic butterfly valve is shown in Figure 2. Its main components include the valve body, valve plate, valve stem, support bearings at both ends of the stem, the stem-to-body seal, the plate-to-body seal, and the hydraulic actuation system.

Figure 2 DN2500 hydraulic butterfly valve structure

The hydraulic butterfly valve was selected for the following reasons:

- It features a compact structure and high cost-effectiveness.

- A hydraulic cylinder drives a crank mechanism to achieve 90° rotation during opening and closing, providing high output torque and rapid actuation.

- It adopts a triple-eccentric metal-to-metal sealing design, resulting in minimal wear of the sealing components.

The main design requirements and parameters of the butterfly valve are as follows:

Working medium: Dry compressed air

Nominal diameter: 2500 mm

Nominal pressure: 2.5 MPa

Operating pressure: 0–2 MPa

Operating temperature range: −10 to 50 °C

Structural configuration: Triple-eccentric metal-to-metal sealed butterfly valve

Installation orientation: Horizontal

Opening and closing time: Adjustable within 3–10 s

Operating frequency: 10–30 cycles per day on average

Flow blockage ratio: Less than 22%

Minimum valve opening ratio: Not less than 3%

Sealing performance: Zero leakage

The overall design concept focuses on optimizing the key valve components while fully meeting the specified design parameters. The structural stiffness and strength are enhanced to ensure long-term, reliable operation under complex and highly variable pneumatic loads. Based on the requirements described above, the key components of the newly developed butterfly valve were designed as follows:

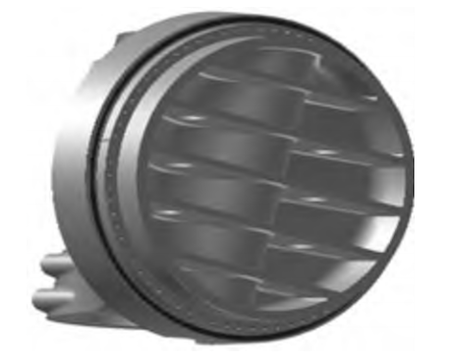

As the most critical component of the triple-eccentric butterfly valve, the butterfly plate was designed to achieve a low flow blockage ratio, enhanced structural stiffness, and stable flow characteristics, as shown in Figure 3. The valve flow passage was enlarged, and the flow diameter at the sealing surface was maximized while minimizing the occupied area. This design increases the effective flow area and reduces flow blockage. The calculated blockage ratio is 17.7%, meeting the requirement of less than 22%.

Figure 3 DN2500 butterfly valve disc

The valve disc incorporates localized stiffness reinforcement, and the effects of internal and external pressure differentials on its structure were fully considered to prevent cracking. A total of 260 pressure-equalization holes, each 22 mm in diameter, were incorporated into the disc, resulting in an opening ratio of 3.5%, which exceeds the 3% opening ratio of the original valve. The valve disc sealing ring is made of 304 stainless steel combined with flexible graphite. The sealing pair consists of the sealing surface on the valve body and the sealing ring mounted on the valve disc. The valve body sealing surface is made of welded stainless steel and then precision ground. The valve disc sealing surface uses a stainless steel–reinforced rubber structure, ensuring reliable sealing performance. The sealing friction angle is 6.56°, preventing interference during valve disc rotation. The valve disc has a streamlined profile on one side and a flat pressure-relief surface on the opposite side. This configuration reduces flow turbulence and maintains flow-field stability.

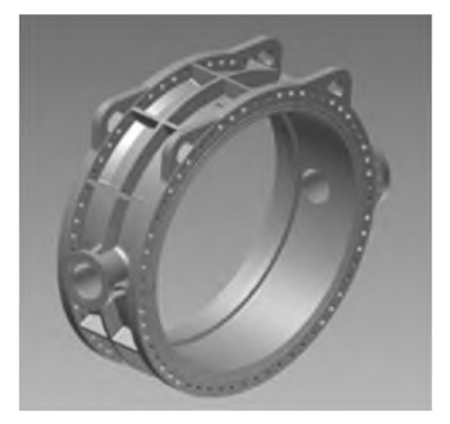

To enhance the valve body’s resistance to pneumatic impact loads and eccentric forces generated during hydraulic cylinder actuation, and to improve its overall load-bearing capacity and stiffness, a high-strength, high-rigidity valve body design was adopted, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4 DN2500 butterfly valve body

The valve body is integrally cast with reinforced circumferential and longitudinal ribs, and the wall thickness has been increased accordingly. According to calculations based on ASME B16.34, the required wall thickness is 47.8 mm. Considering corrosion allowance, the wall thickness was increased from the original 50 mm to 60 mm.

To enhance fatigue resistance and extend service life, both the diameter and material strength of the valve stem were increased. As a critical load-bearing component of the butterfly valve, the stem diameter was increased while ensuring that flow blockage requirements remained satisfied. The calculated stem diameter is 280 mm, and a final diameter of 320 mm was selected to improve engineering reliability. The valve stem is typically made of 20Cr13 stainless steel. However, given the frequent opening and closing cycles in practical operation, 30CrMnSiA high-strength quenched and tempered steel was selected to enhance strength and fatigue performance, thereby extending the valve’s service life. A comparison of the mechanical properties of the two stem materials is presented in Table 1, where R₀.₂ denotes the 0.2% offset yield strength, Rₘ the tensile strength, and HBW the Brinell hardness.

Table 1 Comparison of valve stem materials

|

Material |

R0.2 (MPa) |

Rm (MPa) |

HBW |

|

20Cr13 |

440 |

640 |

192 |

|

30CrMnSiA |

835 |

1080 |

229 |

In addition, the valve stem is supported by JDB self-lubricating bearings made of high-strength brass embedded with graphite. These bearings offer high load-bearing capacity, low friction, and minimal wear, ensuring the valve’s long-term reliable operation.

The hydraulic butterfly valve is actuated by a hydraulic system comprising a drive cylinder, hydraulic oil pipelines, and associated fittings. The system operates at a pressure of 21 MPa, using LHM32 anti-wear hydraulic oil as the working fluid. The selected hydraulic cylinder has the same structural configuration and performance characteristics as the actuator currently used in the wind tunnel. Additionally, a cushioning device is incorporated to mitigate impact loads during valve closure. The opening and closing positions are monitored using independent normally open contacts. Two independent sets of limit switches are installed for the fully open and fully closed positions, and a mechanical travel-limiting device is also provided to ensure operational safety. The valve is installed horizontally, with the hydraulic actuation mechanism positioned on the right-hand side in the direction of airflow. The support bracket for the hydraulic drive unit is designed to provide sufficient strength and stiffness, and an auxiliary support structure is incorporated to withstand the impact forces generated during rapid valve operation.

Stress concentration is a critical factor in valve structural design. Accurate determination of stresses at stress-concentration regions is essential for evaluating both the structural integrity and the fatigue life of the valve. In conventional valve design, the external geometry is first defined to meet operational requirements, followed by numerical simulations to verify structural strength. In this study, the three-dimensional model of the optimized butterfly valve was imported into ANSYS for finite element stress analysis. Due to the asymmetric structure of the hydraulic triple-eccentric butterfly valve, the finite element model retained all primary load-bearing components, while non-load-bearing parts such as the base, support bracket, and actuator were omitted to improve computational efficiency. The final finite element model is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5 DN2500 butterfly valve finite element model

In operation, the hydraulic triple-eccentric butterfly valve is connected to the pipeline at both ends. Fixed constraints were applied to both ends of the valve in the finite element model to represent the actual boundary conditions. The displacement boundary conditions are illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6 Application of boundary conditions

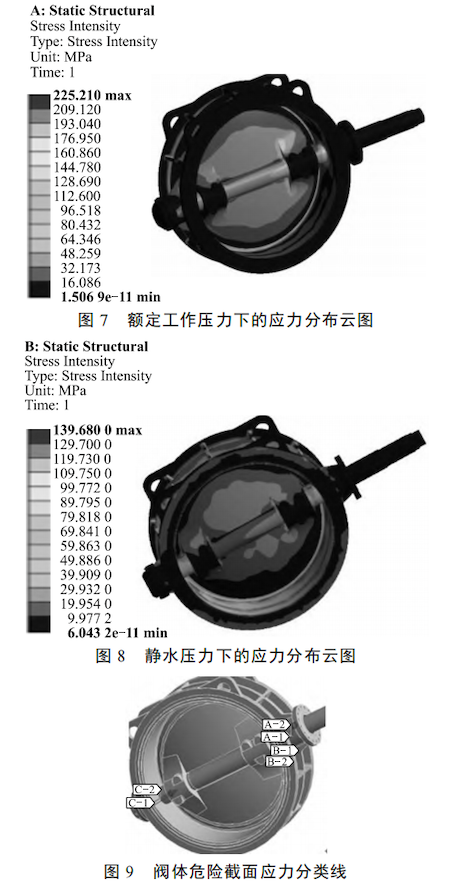

Under rated operating conditions, a pressure of 2.5 MPa was applied to the butterfly plate surface and the internal cavity on the inlet side, and the force exerted by the valve neck on the valve body was 63,030 N. Under hydrostatic test conditions, a pressure of 3.75 MPa was applied to both sides of the butterfly plate and the internal cavity surfaces, resulting in a force of 94,545 N exerted by the valve neck on the valve body. The resulting stress distributions under rated operating and hydrostatic pressures are shown in Figures 7 and 8, respectively. Based on the stress analysis results, stress classification lines A–A, B–B, and C–C were defined at the most critical stress-concentration regions of the valve body, as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 7 Stress contour under rated operating pressure

Figure 8 Stress contour under hydrostatic pressure

Figure 9 Stress classification lines at critical valve body sections

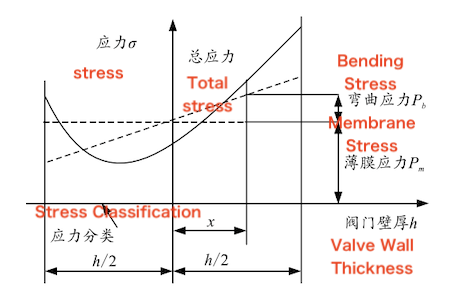

According to strength failure theory, the valve is primarily subjected to membrane and bending stresses. According to stress linearization theory, the total stress at each critical section was decomposed into membrane and bending stress components. The uniformly distributed average stress corresponds to the primary membrane stress Pm, the linearly varying component corresponds to the primary bending stress Pb, and the remaining nonlinear portion represents the secondary stress, as illustrated in Figure 10.

Figure 10 Stress classification and linearization

The stress acceptance criteria are defined as follows: under rated operating pressure, the primary membrane equivalent stress must satisfy Pm≤Sm, and the combined membrane-plus-bending equivalent stress must satisfy Pm+Pb≤1.5Sm. Under hydrostatic test pressure, the criteria are Pm≤0.95Sy and Pm+Po≤1.43Sy, where Sy is the material yield strength and Sm is the allowable stress. The stress evaluation results under rated operating and hydrostatic test pressures are summarized in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

Table 2 Stress evaluation under rated operating pressure (MPa)

|

Section |

Pm |

Pm+Pb |

|

A–A |

28.46 |

60.08 |

|

B–B |

54.71 |

74.89 |

|

C–C |

67.01 |

128.74 |

Table 3 Stress evaluation under hydrostatic test pressure (MPa)

|

Section |

Pm |

Pm+Po |

|

A–A |

14.46 |

21.61 |

|

B–B |

25.53 |

30.03 |

|

C–C |

33.08 |

69.71 |

Under rated operating pressure, the allowable stress is Sm=138MPa, and the corresponding limit for combined membrane and bending stress is 1.5Sm=207 MPa. As shown in Tables 2 and 3, the stresses at all three critical sections under both rated operating pressure and hydrostatic test pressure satisfy the design requirements.

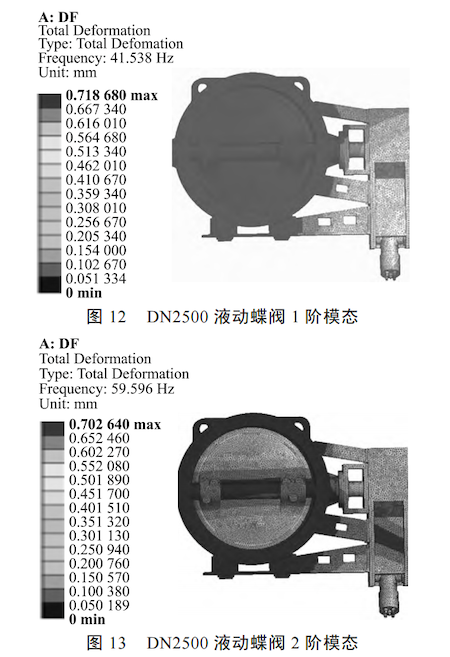

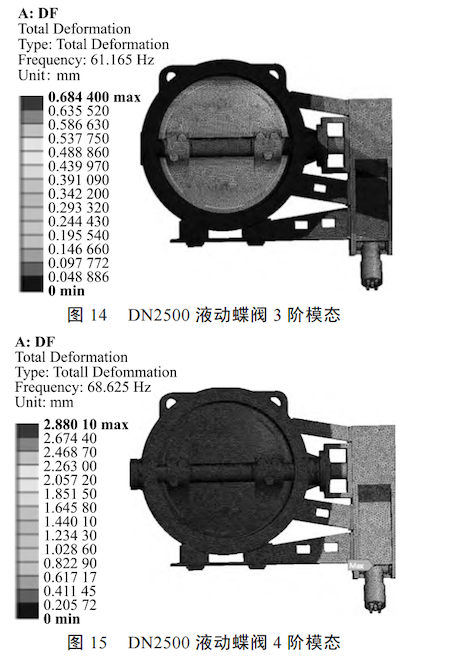

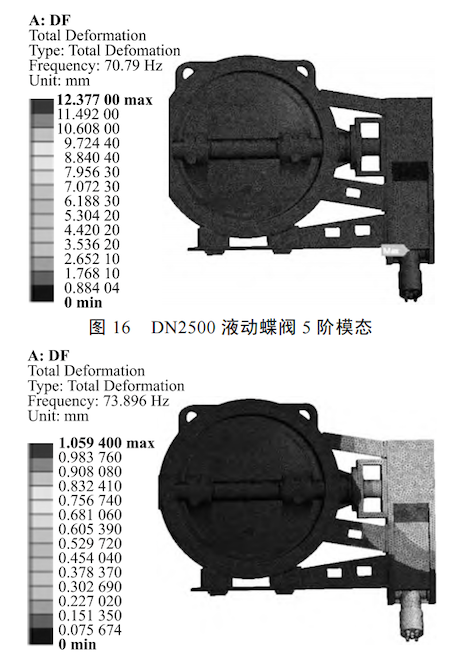

Modal analysis places stringent requirements on mesh quality. Although adaptive meshing can improve meshing efficiency, it may compromise the accuracy of modal solutions. Therefore, during meshing, the software’s built-in adaptive meshing function was combined with targeted manual optimization, taking into account available computational resources and the requirements of the actual engineering problem. The optimized finite element mesh is shown in Figure 11. Figures 12–17 illustrate the first six vibration modes of the DN2500 hydraulic triple-eccentric butterfly valve.

Figure 11 Optimized finite element mesh

Figure 12 DN2500 hydraulic butterfly valve — first vibration mode

Figure 13 DN2500 hydraulic butterfly valve — second vibration mode

Figure 14 DN2500 hydraulic butterfly valve — third vibration mode

Figure 15 DN2500 hydraulic butterfly valve — fourth vibration mode

Figure 16 DN2500 hydraulic butterfly valve — fifth vibration mode

Figure 17 DN2500 hydraulic butterfly valve — sixth vibration mode

Based on the calculation results, the modal frequencies and corresponding maximum vibration amplitudes of the first six modes were extracted and are summarized in Table 4. The results indicate that the vibration amplitudes of the valve at all modal frequencies remain at low levels, and short-term operation at these frequencies is not expected to induce structural damage or impair valve integrity. In practical operation, potential resonance risks can be further mitigated by appropriately extending the valve opening and closing times, thereby avoiding prolonged operation near the natural frequencies listed in Table 4.

Table 4 Modal Frequencies and Maximum Amplitudes of Each Mode

|

Mode Order |

Modal Frequency (Hz) |

Maximum Amplitude (mm) |

|

1st |

61.165 |

0.684 |

|

2nd |

13.896 |

1.059 |

The valve body was subjected to a hydraulic pressure test in accordance with GB/T 13927—2008, Pressure Testing of Industrial Valves. The test was conducted at 1.5 times the design pressure (2.5 MPa), i.e., 3.75 MPa, with a pressure-holding duration of 10 minutes. A sealing test was subsequently conducted at 2.0 MPa (the maximum working pressure) using air as the test medium, with a holding duration of 10 minutes and a specified leakage rate of 0.01 kg/s. The results indicate that both the hydraulic pressure test and the sealing test met the requirements of the standard.

Since commissioning, the DN2500 hydraulic butterfly valve has completed approximately 500 opening and closing cycles, meeting the transient high-speed wind tunnel’s requirements for sealing performance and actuation speed. On-site process tests confirmed that the valve met the design specifications, effectively supporting wind tunnel operations for multiple projects. The engineering test results are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5 Engineering Test Records

|

Test Item |

Test Result |

|

Leakage |

Essentially no leakage |

|

Opening/Closing Time (s) |

3–10 |

|

Opening/Closing Pressure Difference (MPa) |

2.0 (maximum working pressure) |

|

Operating Cycles |

500 (under load) |

|

Operating Duration |

1 month |

Based on the operational characteristics of the butterfly valve and the specific requirements of an intermittent high-speed wind tunnel, the valve was optimized in terms of material selection and structural configuration. Numerical analysis and engineering tests demonstrate that the DN2500 hydraulic butterfly valve meets the expected design specifications, delivers reliable sealing, maintains low flow blockage, and ensures safe and stable operation of the wind tunnel over extended periods. This work provides a valuable reference for the design and application of large-diameter hydraulic butterfly valves in intermittent high-speed wind tunnel applications.